Passing through the countryside in southeast Europe, it’s entirely possible to see massive, alien-like concrete statues looming on the horizon, away from galleries, museums and other traditional art venues. These monuments look mighty and mystical, their somewhat neglected appearance giving an impression they are as old as the planet itself. Yet, most of these spomeniks (literally “monuments”) were constructed in the last 50 years, when they were commissioned by state bodies of the now non-existent country of Yugoslavia. To a casual viewer, their placement and visual character might seem curious, ominous even. However, a brief look at the history of the Balkan peninsula can quickly illuminate the choice in location and artistic style of these unusual memorial statues.

Photo by Andrej

Since the medieval times, the western Balkans has been riddled with conflict. Its geographic positioning made it alluring to all major historical powers of the time: Ottoman Empire, Habsburg Monarchy, Russian Empire and Republic of Venice. The turmoil continued in the first half of the 20th century and culminated during World War II, when the entire region suffered tremendous loss due to a multi-faceted armed conflict. In 1945, the six republics of the peninsula decided to overcome their differences and form a country that would become Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Three major creeds (Roman Catholic, Orthodox Christian and Muslim) and various other smaller ethnic groups called the newly-founded federation their home. Yugoslavia was also a part of the Non-Aligned Movement, distancing itself from the sharply polarized geopolitics of the Cold War era. As the country was still reeling from inter-ethnic conflicts of World War II, Yugoslav authorities had to walk a fine line to ensure all of its citizens felt equal and safe within its borders. “Brotherhood and Unity”, the country’s official slogan, had to be visibly implemented in every aspect of governing and social life.

Photo by Arman Dz.

Photo by Scarix

As it turned out, public works of art became a valuable medium for achieving this goal. They had didactic potential, acting as stark reminders of what happens when fellow countrymen turn into enemies. The memorials were usually built in the countryside, with adjacent hotels, restaurants and museums. Since visits to memorials were highly encouraged by Yugoslav public institutions, these spaces served for leisure, but also historical reconciliation. Moreover, spomeniks had a unifying role, which was achieved through a specific visual style that was free of any ethnic or ideological markings. Yugoslav authorities used existing contemporary art trends and transformed them into a visual expression that would fit country’s peculiar needs. The artistic direction established through this practice was casually referred to as “socialist modernism”; it featured abstract forms, bold constructions and supernatural character.

Photo by Tomislav Medak

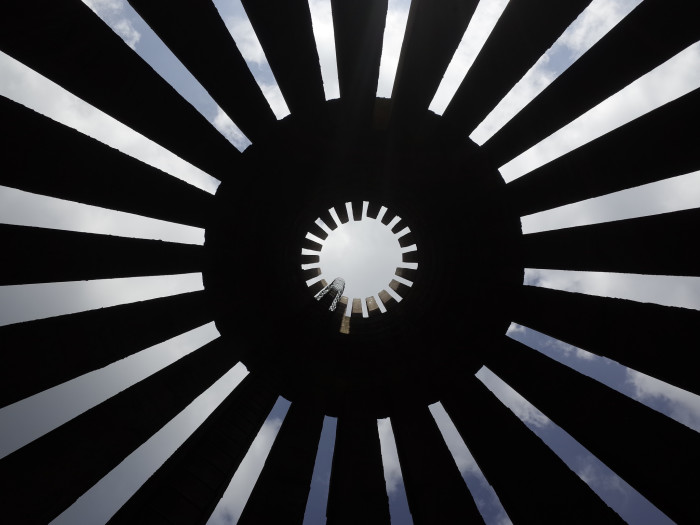

A notable construction born of this movement is the Monument to the Revolution in Mrakovica, present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was designed using 20 unevenly placed segments, which symbolize a play between life and death, light and dark. The openings between these segments are wide just enough to fit one person at a time; once inside, the viewer might experience fear and claustrophobia evocative of the war. Still, it’s worth noting that not all memorial monuments of the Yugoslav era were this somber in character. For example, the 1970 Kosmaj Monument is notably dynamic. It was designed in shape of an enormous spark, marking a symbol of unity and joint future of the Yugoslav people.

Photo by Tomislav Medak

In a tragic turn of events, Yugoslavia broke up in the early 1990s and its dissolution resulted in more deaths caused by multi-ethnic wars. Twenty years later, in the newly-independent republics, spomeniks are nowhere near as visited. Moreover, the country whose tenets they strived to embody is long gone, which further complicates their current interpretation. To some, they represent mammoth relics of a bygone era, a mere historical footnote. However, with regional tensions still fresh in mind, many people continue to see spomeniks as symbols of ideals that are yet to be achieved.

Leave a reply