As electronica darling Richard D James, aka the Aphex Twin, returns to his kingly pedestal with much critical harrumph, something of a tribal clash has emerged on the World Wide Whinge, taking place between two different generations of music fans. In the red corner we have the likes of Aphex Twin and Autechre, the IDM (Intelligent Dance Music) crowd. In the blue corner we have the EDM upstarts, constituting of the likes of Skrillex and Pretty Lights. As members of the former camp see it, EDM has grappled the old vanguard of electronic music in its sweaty haunches, and persists to strangle the life out of the genre with a tight death-lock grip. IDM aficionados claim that EDM is too consumptive, too easy to digest, too safe.

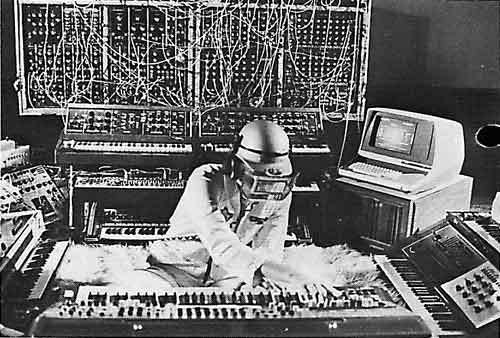

In the late 90s the likes of Aphex and Autechre realized that they had to look backwards in order to move forwards, and so they attempted to partly sever themselves from their more humble rave roots. Many of these artists began to look away from their contemporaries and instead towards the earliest architectures of the genre, towards the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen and Edgard Varèse. In turn, ‘IDM’ was born; a snooty term maintained by the consensus of music journalists, describing an intensely middle-brow music scene the likes of which Aphex Twin would presumably laugh at and ridicule. In reality, ‘IDM’ and EDM exist on a concentric plain. On his Facebook page in 2011, EDM kingpin Skrillex revealed that the Aphex Twin track ‘Flim’ was, and presumably still is, his favorite track of all time. Underneath a Youtube video of the frenetic and melodically perplexing Aphex track, EDM fans, with bald-faced sincerity, wondered aloud via the infamously corrosive Youtube comments section “where’s the drop?” Cue ridicule from those more seasoned fans of electronic music.

While EDM as a term might sound downright clumsy, encapsulating as it does electronic music’s past and present in one fell swoop, Electronic Dance Music remains a suitable catch-all term, marking as it does the genre’s wider incorporation into the musical mainstream. EDM is a direct result of what happens when you take the tools away from those bedraggled professors of sound and democratically elect to pass on the means of production to everybody and anybody. As a result, the genre becomes accessible to participate in, for both the passive listener and also for the active producers of the music. Democracy, at least for some, isn’t good news for innovation; we need the uncompromising technocrats of old to help the genre ‘progress’ into musical pastures new; the machinery needs to be inaccessible, purely untouched by plebeian hands.

It’s easy to sneer at EDM as a collective scene whilst overlooking the more plus-positive aspects of the genre. While much of the music itself is not, at least in its present incarnation, particularly innovative, the methods in which these artists are taking to produce and also market their tracks most certainly are. These techniques are either incidental bi-products of the music, or intelligent business strategies forged with a conscientious sense of purpose by the artists themselves. More than simple purveyors of drops and bloops, these producers and songwriters are currently pushing the perimeters of how the music industry operates on a larger scale, sheerly by stressing a reliance on these new and continuously emerging internet-based business models. In between producing bangin’ tracks, these laptop-wielding, business-savvy entrepreneurs also know the inherent value of PR and social marketing.

Today, DJs and electronic producers are artists as much as they are business men, taking up a unique status in a newly emergent self-made industry, which in turn allows them to live a lifestyle of gloss and glitz. Through the likes of Soundcloud and Bandcamp, the goal is to achieve a degree of popularism on the net, which in turn leads to further success on the club scene. Down the road, success in both of these realms allows artists to skip the middle-men of the recording industry altogether to manage their “business” purely on their own terms. If you’re a recording artist today, having a commercial strategy is not simply a dirty, shameful compulsion, it’s an entirely necessary pre-requisite for success in both the industry and the club circuit at large; you need to be a strategic thinker in order to thrive. The shrinking violets, vulnerable ‘artistes’ and surreptitious talents of old are required to develop a more pragmatic mentality in order to survive in the industry today; a tougher skin is demanded.

For those that make it, many are in a sense self-made; an achievement that offers a panoramic view of the perimeters of the current music scene. These artists are able to perceive on a grander scale from the unique vantage point of the high-rise blocks of their musical enterprises. The benefit of such a scope allows these artists to develop a more nuanced view of the bigger picture: they have truly gone freelance, and as such, an entrepreneurial spirit has imbued the genre. The most successful of the bunch wind up creating their own labels, invariably christening them with irreverent, piss-takey titles, such as La Castle Vania’s ‘Fuck Yesss’ label, which, more than just a run of the mill music label, is also badged as a ‘dance party and entertainment brand.’ Increasingly, the middle-men of the music industry are being discarded for these new self-made ventures, further encouraged by newly emergent business models which value individuality and the undiluted voice of the artist. As a direct result, artists themselves are wresting control of the wheel to the point where they can market themselves without the restrictive perimeter walls of the old school record labels. The likes of Twitter and Facebook further emphasize these self-made strategies, forging as they do a direct line from the artist to the fans –or, to put it more mechanically, from producer to consumer. Given that these revolutions in marketing were designed and implemented on computer systems, all in the name of ‘going viral,’ it’s no coincidence that EDM artists are utilizing these strategies more effectively than your typical blues rock revival band.

Subsequently, we have a scene where art and commerce find themselves not as strict counterparts, but as partners on a dual course. In terms of the music itself, EDM is less an individualist’s genre, more the sound of a collective working together and off the back of one another creatively. We are all cyborgs now, and in turn there’s a wider compulsion for EDM artists to form an Apple-style sense of identity maximizing the sheer ubiquity of the genre. The pervasiveness of The Cloud has infected our mindsets, both in how we think of and also through how we produce music; we now ought to boast of the benefits of collectivity and collaboration: derivative music making has become an industry aesthetic of sorts. Inevitably, and with good reason (after all, it’s a matter of taste), some may deride this uniformity in sound as an unsavory and bland form of conformism. Perhaps this is an inevitable result in a climate where artists are now also wrapped up in the more extra-curricular, commercial sides of music making. We have to remind ourselves that the Internet doesn’t just foster talent, it melds the creative sides of music making with the end result of capital gain, rendering the two inseparable. The result is that art and commerce, as Andy Warhol foresaw it, have inextricably entwined; the advert has become art form. All we can do, for now, is persist with it and see where it leads us.

saytek blog

For those who are fed up with EDM, it’s difficult to pinpoint where the commercial aspects end and where the artistry begins. When the likes of Pretty Lights and Skrillex are performing their latest singles in clubs, it seems fair to reason that they’re also performing an extensive act of brand awareness for their own ‘You Sucked My Battledick’ musical enterprises. This is not simply a question of sincerity, it’s how the most evolved minds in the industry now think – perhaps the key to making it in the industry is to go to business school, rather than studying music at diploma level. While the old vanguard of the music industry remains in search of a more concrete range of online-based solutions in order to become commercially viable again, these artists are at least attempting to forge a new path.

Similarly, another merited question is: where does programming end and performance begin? There is certainly an element of postmodern hucksterism in much EDM, the likes of which I don’t find attractive, personally. We have to question a music scene whose most respected proponents, such as Pretty Lights, are lauded as ‘innovators,’ simply for reverting back to the old-fashioned methods of recording. In the liner notes of his most recent LP, A Color Map of the Sun, Derek Smith, aka Pretty Lights, had the gumption to label his purposefully recorded live sounds ‘samples,’ leaving fans to ruminate on his brilliance as a sonic inventor, rather than his more obvious PR skills at re-naming the very term ‘sample.’ These ‘samples’ were merely riffs that he had lifted from previous recording sessions, which were then purposefully laid down on his own electronic tracks. A sample, recorded in hindsight, or snagged from somebody else’s record, is still just a sample.

Whereas Kraftwerk added a conceptual bent to their pioneering brand of electronic music, playing like human-machines in the aim to reflect what they saw as the de-humanization of society in a newly post-industrialized world, we now find ourselves on the flip-reverse: the machines are playing their darnedest in an attempt to sound like flesh and blood humans. Drops are deployed with clinical finesse for a range of Satisfaction Enjoyment Optimization schemes, surrounded by so much audio bluster. Perhaps this is an inevitable result in a climate where artists find themselves increasingly wrapped up in the commercial sides of music making, but to write these changes off as purely negative attributes seems to be short-sighted and unimaginative. This literal bridging together of the worlds of commerce and art may be seen as a soulless and depressingly staid development for some, or as an all-inclusive, vivid and intensely lively proceeding for others. Really, it all depends on your overall appreciation of the music itself.

Leave a reply